I’ve been working on this essay on and off for about four months and it’s gone through countless edits and revisions. I don’t have the energy to make it better so it is what it is. Apologies for typos and any issues with flow but I didn’t want to put off publishing it any longer. There are other things I want to write. Hope it all makes sense, it was a nightmare pulling it out of my brain.

Have you ever noticed that, these days at least, most therapists are not offering intervention to modify unhelpful thoughts and behaviour, and are instead focused on listening to and affirming the client? This is the difference between psychotherapy and talk therapy, respectively, according to clinical psychologist Dr. Roger McFillin, which he explored in a June Substack post. He wrote that being a good listener and keeping a conversation going are useful skills, but the problem is that “general counselling or ‘talk therapy’ is being slapped on everyone, no matter what their issue is or how bad it’s gotten. It’s like a one-size-fits-all approach, and we know that doesn’t work for shoes, let alone mental health.”

McFillin’s essay echoed many of my own thoughts about how modern therapy has devolved into a “watered-down version of what it’s supposed to be.” He explained:

“What we often see now is the therapist passively steering the client through a meandering stream of consciousness, occasionally tossing in reflection or a bit of feedback” […] “It most certainly is not the targeted behavioural treatments for severe clinical disorders. Instead, it’s become a sort of weekly review, where the therapeutic value is assumed to lie in the mere act of talking things out. The therapist, in this model, functions more as a sounding board than as an active agent of change. They might offer the occasional insight or validation, but there’s often a lack of structural intervention or targeted skill-building. This passive approach can create an illusion or process without necessarily addressing the core issues of equipping clients with the tools they need to navigate their challenges effectively.”

Most therapists on Psychology Today “claim a remarkably broad range of expertise. They list everything from severe conditions like bipolar disorder to more common issues like relationships…” McFillin adds that, while it’s great that many therapists have a masters in counselling or social work, “it doesn’t exactly prepare them with a science based education and expertise to intervene [in] really severe and debilitating conditions.”

When I decided to try private therapy, my therapist never took any initiative in leading or directing the sessions, let alone suggesting any thought or behavioural modifications. She focused, instead, on affirmation, which was lovely but it wasn’t going to help me move forward. When I asked for more structure, she failed to provide it. I stopped seeing her for the simple fact that we weren’t really doing anything. She was one of the many therapist profiles that claimed broad expertise, but I suspect that the majority of them either don’t possess it or struggle to implement it. Offering knowledge of many therapies to treat severe conditions like personality disorder or bipolar disorder, only to be met with passive counselling is crushing.

The popularity of the term “trauma-informed,” which arose during the COVID-19 pandemic, has contributed to these problems. It seems that a lot of trauma-informed therapists only have one skill: affirmation. This is incredibly important for people struggling with their mental health, especially trauma survivors, but it’s useless if you cannot help the client develop the skills and confidence to eventually move forward with their lives. Many of there therapists are lovely people with a genuine desire to help others, but they are largely ineffective when they cannot bring about any meaningful change and leave the client stuck in an increasingly worsening spiral.

Therapy is often touted as good for everyone, something we all should do. I used to agree but now I’m not so sure. McFillin said, “Therapists, intentionally or not, have created a perfect business model: clients who aren’t struggling enough to require treatment, but are convinced that they need constant professional help to navigate life’s normal stressors.” This leads to people developing learned helplessness: feeling unable to deal with life’s normal up and down without someone else’s input. It removes your agency and ability to trust and care for yourself. While I’ve struggled with severe mental health problems, I definitely relate to this one. It’s great to have someone to talk to, a sounding board as McFillin said, but at what point do we call it a day?

***

“Anxiety’s central task, as instructed by fear, is to run ahead and touch everything, circle potentialities with the intention or preventing them from happening, on and on and on in a process that never stops, that becomes one with life. […] She was never granted peace, there was always some aspect of the world that had to be controlled lest things got out of hand. And I suppose that’s what’s at the heart of it from every person suffering from anxiety; the fact that life, by its very nature, is impossible to manage.” — Ia Genberg, The Details.

Even when psychotherapy like cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is carried out well, it can lead to another problem: the intellectualisation and dismissal of one’s emotions. CBT is defined by the NHS as a talking therapy that can help you manage your problems by changing the ways you think and behave. It’s based on the idea that your thoughts, feelings, physical sensations, and actions are all interconnected, and that negative thoughts and feelings trap you in a negative cycle. In reality, CBT tends to focus solely on changing negative thoughts and reminding you that your thoughts and feelings are not facts. These are valuable skills and lessons, but for many they often come at the expense of dismissing your emotions entirely.

In July, Dr. McFillin posted a Substack essay talking about our obsession with anxiety and how our reaction to it makes it worse: “By treating normal emotions as disorders to be eliminated, we’ve created a paradox where the very fear of experiencing anxiety fuels more anxiety.” This is the very thought pattern that drives panic disorder, something I am diagnosed with. The fear of a panic attack often creates more panic attacks, and so behaviours are developed in order to reduce the risk of experiencing one.

McFillin went on to explain that “we’ve conditioned ourselves to view anxiety as an enemy to be vanquished, rather than a natural part of the human experience. This mindset turns every flutter into a potential crisis, keeping people constantly on edge, waiting for the other shoe to drop. The result? A perpetual state of hypervigilance that exhausts the mind and the body, ironically making us more susceptible to the very thing we’re trying to avoid.” Growing up, I learnt (from my parents and society at large) that my intense emotions were a sign of weakness and it was better to be an emotionless person who is seemingly unaffected by anything, and so that is who I tried to become—but I’m simply not that person. All of that emotional suppression came out in physical symptoms such as IBS, POTS, and panic attacks. When these became more frequent and extreme, I focused solely on the physical symptoms, which only increased my fear of experiencing any discomfort—even from normal bodily functions. And this growth of fear is exponential. It takes over your life, seeping into every crack like poison. Before I knew it, my world was remarkably small and I was too scared to do anything—even existing in my own body is a battle.

Sometimes, it feels like the purpose of CBT is to avoid feeling anything at all, but that isn’t true. The problem is that mental health services are providing inadequate treatment and are often encouraging rumination and intellectualisation in those with severe mental health problems. When none of my CBT skills were working anymore, I blamed myself. I had so much emotion and physical sensation happening inside my body and I didn’t know what to do with it anymore. I wanted to turn my emotions off, but this build-up was a result of already trying to do that and it not working. I became stuck in a spiral of deep and compulsive rumination to try and “fix” whatever was wrong so I could not experience it. My goal wasn’t even to feel good, it was to feel nothing.

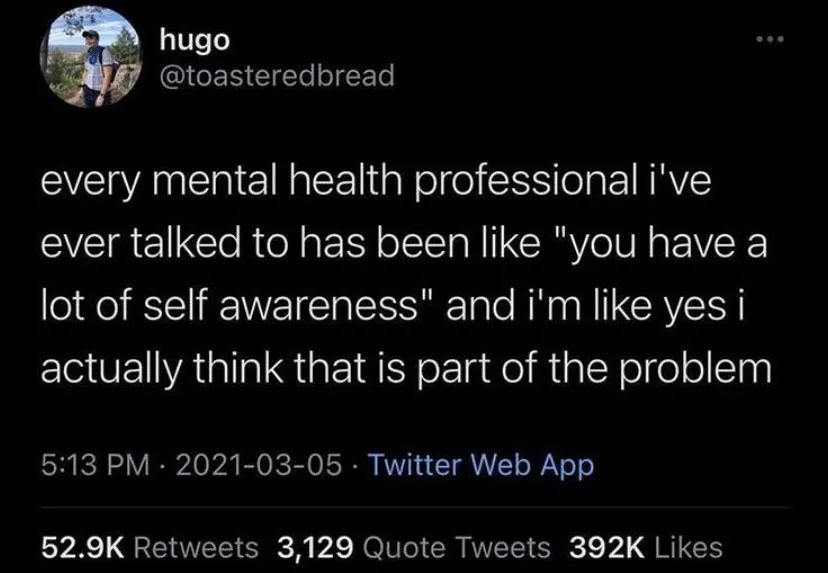

This was something that therapists—and other mental health professionals—were largely not picking up on, likely due to lack of training or the fact that it can just be hard to identify. I was good at hiding it because I sounded “intelligent” and “self-aware,” which are words I’ve heard countless times from therapists who didn’t know what else to do with me. This is a common experience. There are plenty of online memes where therapists tell their clients you’re so self-aware, and the client says yes, I think that’s actually part of the problem. But has anyone actually said that to their therapist? Because you should. Being self-aware is often just rumination in disguise. What tools do you have to get out of it?

***

Last year, I began CBT for panic disorder, but it wasn’t helping—a conclusion both myself and my therapist came to. He said that because I have complex emotional needs (aka borderline personality disorder), I experience emotions more intensely which can impact the efficacy of other treatments. He suggested dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) for stabilisation, a program my community mental health team (CMHT ) only introduced in January 2024. This meant I had to have another mental health assessment, over four sessions, to determine if DBT would be suitable, or if something else might be more appropriate instead. I was shocked by the outcome, which was to be discharged back to my GP after four years under secondary care. In this time, I only had two treatments, both of which failed.

The psychologist said that while I don’t fully meet the criteria for DBT, they would let me do it because of my presenting problems with emotional regulation and distress tolerance. She did, however, express concern that it might make me feel the way I do now, which is thinking that no therapy is going to help me and that it’s my fault. The psychologist also told me that there was nothing she could teach me that I didn’t already know. I knew emotional regulation and distress tolerance skills. And I did them. Still do. I’ve been in and out of therapy since I was 19, and when I became really sick in late 2016, I began researching mental and physical health extensively, something that has only reduced drastically in the last few years due to burnout and a strong desire to stop ruminating and searching for some miracle cure. I know a lot, but I don’t know everything. If anything, all of this learning became overwhelming because it revealed to me just how much I didn’t know. It also makes you feel more worthless when you know what would help but you struggle to do it and be consistent with it due to the very nature of your difficulties. Ignorance is bliss.

While I know a lot about DBT, I don’t know everything about it nor do I know how to implement what I do know. DBT is also geared towards people who have under-controlled temperaments and are therefore more likely to be impulsive and emotionally explosive. They are ruled by their emotional mind. While I have my moments, I am much more rational-minded which comes at the expense of my emotional health. CBT only strengthened my capacity for rational thought, which is one of the problems I found with doing it when I didn’t need help with skills like problem solving anymore. Focusing on rational thought means you’re always able to dismiss your own emotions because you recognise the thought patterns as black or white thinking or catastrophizing and so forth. It’s ammunition for your harsh inner critic. There you go, you stupid shit, catastrophizing once again.

In DBT, there’s a skill called “wise mind” which is the ability to balance your emotional and rational mind. While I’ve had this roughly explained in an emotional coping skills group, I’ve never been officially taught it. I don’t feel able to do it because I’m too busy rationalising, calling myself names, and trying to make my emotions disappear. I don’t know how to effectively interrupt this cycle, especially because I don’t trust myself to be able to discern what is an appropriate way to think or behave (there’s a chance I’m autistic). This keeps me stuck, as does my assertiveness because I think it often comes out as unintentionally mean. It gets even harder when I do express my emotions to someone through what I think is a rational lens and I am frequently met with them rationalising things out while dismissing my emotions. In our society, this is normal and CBT reinforces that. DBT, however, offers a way to acknowledge both reason and emotion—but you can’t control other people.

During my assessment sessions, I tried my best to be as honest as possible while quickly summarising all my major problems. When I thought about what might be getting in the way of treatment, I brought up my ability to rationalise everything. I will often not bring up hurt feelings because I know that person was probably just tired and didn’t mean it, so it’s not worth even having the conversation in the first place. It helped that the psychologist noticed this in real time when she asked me how I felt about something and I responded by intellectualising my emotions. I told her how scared I was of feeling my own emotions in my body, as well as other sensations, and how no one is helping me with that. This led her to wonder if I rely on services and other people too much to make me feel better because I lack the confidence to do it for myself. While I suffer in silence for as long as possible, and only reach out when I’m at my limit, what she said was true.

When in crisis, I prefer someone else to be there. It feels like a lifeline because I don’t feel like I can cope by myself. It’s not easy to reach out nor do I reach out every time, because paradoxically I find mental health services, including the crisis team, quite unhelpful. The psychologist said that when people show up in crisis, the professional usually wants to “fix” and “save” the client. I said that, for me, I no longer want instructions. I already know what to do. Instead, I want the comfort (emotional attunement) and sense of safety that I didn’t receive in my childhood as I now find it difficult to create that for myself. I want to be told that I will be okay. (My CBT therapist once saying I don’t know that. I don’t know if you’ll be okay, as a way to target fear of the unknown was NOT helpful btw!) I agreed to be discharged so I can develop my own sense of safety and the capacity to trust that I can take care of and comfort myself.

I think that during and after therapy many of us develop the false belief that being aware you’re mindreading or jumping to conclusions means that you eventually shouldn’t have any negative thoughts at all, and if you do then you’re doing it wrong because you’re a big dumb idiot. Many of us also develop the false belief that regulating and tolerating our emotions means getting rid of them, and if you’re still being overwhelmed by strong, negative emotions, then you’re doing it wrong and, again, you’re a big dumb idiot. These are things I’ve believed, at least, and it makes me feel kinda stupid. (Yes, I’m also working on targeting my harsh inner critic!) It ties back into McFillin’s point about how we’ve built emotions up as monsters to be eliminated, when in reality we need to learn to live alongside them without them running the show and taking over our whole lives. FYI: Tolerating emotions isn’t the same as allowing them.

***

When I saw my CBT therapist in August to say goodbye, I asked him if he had any advice for what I could do for myself to overcome panic disorder. He said that I need to be able to tolerate other emotional states first because panic is obviously extremely overwhelming. This made me feel disappointed and dejected, just like I had when we realised I wasn’t responding to treatment. I try my best to go with the current instead of against it, but it’s just so intense that I often wish I would explode just so I could feel some relief. I remember thinking that I’m never going to overcome panic if I can’t tolerate the intensity of any emotion, including normal physical sensations. One thing I know for sure is that I’m never going to get better hyperfocusing on my symptoms and partaking in metacognition. Despite the therapy not being helpful, this CBT therapist was the first person to identify panic disorder (something that should not have taken the CMHT three years to recognise) which has helped tremendously.

Panic disorder is technically easy to treat, but for me it’s tricky because it has been going on for a long time and co-existing conditions affect how I experience it. Treatment involves removing the fear around the physical sensations of panic. It took me reading two things for something in me to really change. One of these was that your nervous system creates how you feel; your thoughts and feelings, the state of your body. It does this by constantly scanning for threats and collecting information, which it started doing while you were still in the womb. When I feel overwhelmed by my emotional and physical state, I think about how much I feel relates to the past but is not the truth for right now. Knowing the loose science behind it, beyond the knowledge that your nervous system is hypervigilant, really changed the way I thought about fear and has allowed me to better target it.

Mental illness recovery is difficult but it’s particularly strange when you’re simultaneously getting a glimpse of the good that life can be and the bad that life has been for so long. Both are scary, but only one is familiar. Currently, I am handling panic much better. In August (I think), I had two panic attacks that happened while I was alone and lasted the usual few hours, but this time they didn’t traumatise me. It was hard and I was scared at times, I still took diazepam eventually, but the experience was nowhere near as bad as it usually is. Since then, I have continued to have limited symptom attacks (aka a wave of panic that floods but immediately leaves). I have coped with these even better and prevented them from becoming full blown panic attacks. It can still be terrifying, but I’m doing my best to remove the fear from the sensations. I am also easily overwhelmed by normal sensory experiences, so I’m working on that, too.

It’s inevitable that panic will get me at some point, and maybe I won’t cope as well, especially if I’m visited by the three horsemen of the apocalypse: dread, despair, and hopelessness. But I need to get up again. And again. And again. Just like I always do. Even if sometimes I’m down for longer, I still get back up. It doesn’t have to be like this forever. It takes time to rewrite old data (aka create new neural pathways), but I feel closer to understanding myself, how I got here, and seeing a way out of my problems, and I’m going to do it.